Adam Smith’s Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations opens by discussing the division of labour. How people are able to get more done when they each pick a small part of the work to be done and focus on that, trading their results with others to gain access to the common wealth. He goes on to explain that while what people are really trading is labour, it’s hard to think about that so the more comprehensible stand-in of money is used instead.

Smith’s example is a pin factory, where one person might draw out metal into wire, another cut it to length, a third sharpen one end, a fourth flatten the opposite end. He says that there is a

great increase in the quantity of work, which, in consequence of the division of labour, the same number of people are capable of performing

Great, so dividing labour must be a good thing, right? That’s why a totally post-Smith industry like producing software has such specialisations as:

Oh, this argument isn’t going the way I want. I was kindof hoping to show that software development, as much a product of Western economic systems as one could expect to find, was consistent with Western economic thinking on the division of labour. Instead, it looks like generalists are prized.

[Aside: there really are a few limited areas of specialisation, but then generalists co-opt their words to gain by association a share of whatever cachet is associated with the specialists. For example, did you know that writing UNIX applications makes you an embedded programmer? Another specialisation is kernel programming, but it’s easy to find sentiment that it’s just programming too.]

Maybe the conditions for division of labour just haven’t arisen in programming. Returning to Smith, we learn that such division “is owing to three different circumstances”:

- the increase of dexterity in every particular [worker]

This seems to be true for programmers. There is an idea that programmers are not fungible resources, and that the particular skills and experiences of any individual programmer can be more or less relevant to the problems your team is trying to solve. If all programmers can truly be generalists, then programmers would basically be interchangeable (though some may be faster, or produce fewer defects, than others).

Indeed Harlan Mills proposed that software teams be built around the idea that different people are suited to different roles. The Chief Programmer Team unsurprisingly included a chief programmer, analogous to a surgeon in a medical team. As needed other specialists including a librarian, technical writers, testers, and “language lawyers” (those with expertise in a particular programming language) could be added to support the chief programmer and perform tasks related to their specialities.

- the saving of time which is commonly lost in passing from one species of work to another

Programmers believe in this, too. We call it, after DeMarco and Lister, flow.

Which leaves only one place in which to look for a difficulty in applying the division of labour, so let’s try that one.

- to the invention of a great number of machines which facilitate and abridge labour

So we could probably divide up the labour of computing if only we could invent machines that could do the computing for us.

Hold on. Isn’t inventing machines what we do? Yet they don’t seem to be “facilitating and abridging labour”, at least not for us. Why is that?

At the technical level, there are two things holding back the tools we create:

-

they’re not always very good. Building your software on top of a tool as a way to save labour is perceived as a lottery: the price is the labour involved in working with or around the tool, and the pay-off is the hope that this is less work than not using the tool.

-

they only really turn computers into other computers, and as such aren’t as great a benefit as one might expect. We’re trying to get to “the computer you have can solve the problem you have”, and we only really have tooling for “the computer you have can be treated the same way as any other computer”. We’re still trying to get to “any computer (including the one you have) can solve the problem you have”.

This last point demonstrates that the criterion of facilitating and abridging labour is partially solved. The goal of moving closer to the end state, where our automated machines help with solving actual problems, seems to have come up a few times (mostly around the 1980s) with no lasting impact: in object-oriented programming, artificial intelligence and computer-aided software engineering; specifically Upper CASE.

Why not close that gap, particularly if there is (or at least has been) both academic and research interest in doing so? We have to leave the technology behind now, and look at the economics of software production. Let’s say that computing technology is in the middle of a revolution analogous to the industrial revolution (partly because Brad Cox already went there so I don’t have to overthink the analogy).

The interesting question is: when will we leave the revolution? The industrial revolution was over when mechanisation was no longer the new, exciting, transformative thing. When the change was over, the revolution was over. It was over when people accepted that machines existed, and factored them into the costs of doing their businesses like staff and materials. When you could no longer count on making a machine as a profitable endeavour in itself: it had to do something. It had to pay for itself.

During the industrial revolution, you could get venture capital just for building a cool-looking machine. You could make money from a machine just by showing it off to people. The bear didn’t have to dance well: it was sufficient that it could dance at all.

We’re at this stage now, in the computer revolution. You can get venture capital just for building a cool-looking website. Finding customers who need that thing can come later, if at all. So we haven’t exited the revolution, and won’t while it’s still possible to get money just for building the thing with no customers.

How is that situation supported? In Smith’s world, the transparent relationship between supply and demand drove the efficiency requirements and thus the division of labour and the creation of machines. You know how many pins you need, and you know that your profits will be greater if you can buy cheaper pins. The pin factory owners know how many employees they have and what wages they need, and know that if they can increase the number of pins made per person-time, they can sell pins for less money and make more profit.

How do supply and demand work in software? Supply exists in bucketloads. If you want software written, you can always find some student who wants to improve their skills or even a professional programmer willing to augment their GitHub profile.

[This leads to another deviation from Adam Smith’s world, but one that can be left for later: he writes

In the advanced state of society, therefore, they are all very poor people who follow as a trade, what other people pursue as a pastime.

This is evidently not true in software, where many people will work for free and others are very well-paid.]

There’s plenty of supply, but the demand question is trickier to answer. In the age of supply, not demand Aurel Kleinerman (via Bob Cringely) suggests that supply is driving demand. That people (this seemingly limitless pool of software labour) are building things, then showing them to people and seeing whether they can find some people who want those things. I think this is true, but also over-simplified.

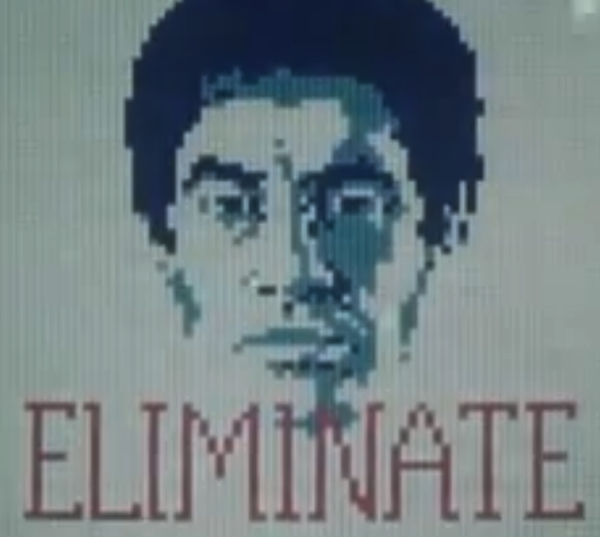

It’s not that there’s no demand, it’s that the demand is confused. People don’t know what could be demanded, and they don’t know what we’ll give them and whether it’ll meet their demand, and they don’t know even if it does whether it’ll be better or not. This comic strip demonstrates this situation, but tries to support the unreasonable position that the customer is at fault over this.

Just as using a library is a gamble for developers, so is paying for software a gamble for customers. You are hoping that paying for someone to think about the software will cost you less over some amount of time than paying someone to think about the problem that the software is supposed to solve.

But how much thinking is enough? You can’t buy software by the bushel or hogshead. You can buy machines by the ton, but they’re not valued by weight; they’re valued by what they do for you. So, let’s think about that. Where is the value of software? How do I prove that thinking about this is cheaper, or more efficient, than thinking about that? What is efficient thinking, anyway?

Could it be that knowledge work just isn’t amenable to the division of labour? Clearly not: I am not a lawyer. A lawyer who is a lawyer may not be a property lawyer. A lawyer who is a property lawyer may only know UK property law. A lawyer who is a UK property lawyer might only know laws applicable to the sale of private dwellings. And so on: knowledge work certainly is divisible.

Could it be that there’s no drive for increased efficiency? Maybe so. In fact, that seems to be how the consumer economy works: invent things that people want so that they need money so that they need to work so that there are jobs in making the things that people want. If it got too easy to do middle-class work, then there’d be less for the middle class to do, which would mean less middle class spending, which would mean less demand for consumer goods, which would… Perhaps knowledge work needs to be inefficient to support its own economy.

If that’s true, will there ever be a drive toward division of labour in the field of software? Maybe, when the revolution is over and the interesting things to create for their own sake lie elsewhere. When computers are no longer novel technology, but are simply a substrate of industry. When the costs and benefits are sufficiently well-understood that business owners can know what they need, when it’s done, and how much it should cost.

That’ll probably be preceded by another software-led recession, as VCs realise that the startups they’re funding are no longer interesting for their own sake and move on to the (initially much smaller) nascent field of the next revolution. Along with that will come the changes in regulation, liability and insurance as businesses accept that software should “just work” and policy adjusts to support that. With stability comes the drive to reduce costs and increase quality and rate of output, and with that comes the division of labour predicted by Adam Smith.