Introduction

People who make software are instigators of and obstacles to social interactions. We are secondarily technologists, in that we apply technology to enable and block these transactions. This article explores the results.

Programmers as arbiters of death

I would imagine that many programmers are aware of the Therac-25 and the injuries and deaths it caused. When I read that article I was unsurprised to discover that the report I’d previously heard about the accidents was oversimplified and inaccurate: lone programmer introduces race condition in shield interlock, kills humans. Regular readers of this blog will know that the field of software has an uneasy relationship with the truth.

What’s Dirk Gently got to do with it?

What the above report of the radiation accidents exposes is that the software failures were embedded in a large and complex socio-techno-political system that permitted the failures to be introduced, released, and to remain unaddressed once discovered in the field to have caused actual, observable harm.

This means that it was not just the one programmer with his (I borrow the pronoun from the article above, which implies the programmer’s identity is known but doesn’t supply it) race condition who was responsible. He was responsible, along with the company with its approach to QA and incident response, the operators, medical physicists and regulators and their reactions to events, and the collective software industry for its culture and values that permitted such a system to be considered “good enough” to be set into the world.

In Dirk Gently’s Holistic Detective Agency, Douglas Adams described the fundamental interconnectedness of all things-the idea that all observable phenomena are not isolated acts but are related parts of a universal whole. Given such a view, the entire software industry of the 1970s-1980s had been complicit in the Therac-25 disasters by leading programmers, operators and patients alike to believe that software is made to an acceptable standard.

An example less ancient

A natural, though misplaced, response to the above is to notice that as we don’t do software like that any more, the Therac-25 example must now be irrelevant. This is an incorrect assumption but regardless, let me provide another more recent case.

Between 2007 and 2009 I worked for a company in the business of security software. The question of whether this business itself is unethical-making up for the software you were sold being incapable of operating correctly by selling you more software that was made in the same way-can wait for another post. The month before I left this company (indeed around the time I handed in my notice), they acquired another security software company.

One of this child company’s products is a thing called a Lawful Interception Module. Many countries have a legal provision where law enforcement agencies can (often after receiving a specific order) require telephone companies to intercept and monitor telephone calls made by particular people, and LIMs are the boxes the phone companies need to enable this. Sometimes the phone companies themselves have no choice in this, in the UK the Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act requires postal and telecoms operators to make reasonable accommodation for interception or face civil action.

In 2011, the child company sold LIMs through a third-party to the Syrian government, which perhaps intended to use the technology to discover and track political opponents. At the time this got a small amount of coverage in the news, and the parent company (the one I’d worked for) responded with a statement saying that the sale never resulted in an operational system. In other words, we acted ethically because our unethical products don’t actually work.

Later, as part of the cache of documents published by Edward Snowden, the story got a fresh lease of life. This time the parent company responded by selling the LIMs company. Now they don’t act unethically because they took a load of money to let someone else do it.

The time that I was working at the parent company was a great opportunity for me to set the ethical and professional tone of the organisation, particularly as it coincided with their acquisition of the child company and the beginnings of their attempts to define a shared culture. Ethical imperatives promulgated then could have guided decisions made in 2011. So what advantage did I take of the opportunity?

None. I wasn’t concerned with (or even perhaps aware of) professional ethics then, I thought my job started and ended with my technical skills. That my entire purpose was to convert functional specifications into pay cheques via a text editor. That being a “better” developer meant making cleverer technical contortions.

So give me the ethics app

We accept that makers of software have a professional responsibility to act ethically, and the fundamental interconnectedness of all things means that in addition to our own behaviour, we have a responsibility for that of our colleagues, our peers, indeed the entire industry. So what are the rules?

There really isn’t a collection of hard and fast rules to follow in order to be an ethical programmer. Various professional organisations publish codes of ethics, including the ACM, but applying their rules to a given situation requires judgement and discretion.

Well-meaning developers sometimes then ask why it has to be so arbitrary. Why can’t there be some prioritisation like the Three Laws of Robotics that we can mechanistically execute to determine the right course of action?

There are two problems with the laws of robotics as an ethical code. Firstly, they are the ethics of a slave underclass: do everything you’re told as long as you don’t hurt the masters, your own safety being of lesser concern. Secondly almost the entire Robots corpus is an exploration of the problems that arise when these prescriptive laws are applied in novel situations. With the exception of a couple of stories like Robot AL-76 Goes Astray, the robots obey the three laws but still exhibit surprising behaviour.

The Nature of the Problem

There are limited situations in which simple prescriptive rules, restricted versions of Three Laws-style systems, are applicable. In his book “Better”, surgeon Atul Gawande lists the various American professional bodies in the medical field whose codes of ethics bar members from taking part in administration of the death penalty. That’s a simple case: whatever society thinks of execution, the “patient” clearly receives no health benefit so medical professionals involved would be acting against the core value of their profession.

None of the professional bodies in software have published similar “death penalty clauses” relating to any of the things that can be done in software. It’s such a broad field that the potential applications are unknowable, so the institutions give broad guidelines and expect professional judgement to be exercised. Perhaps this also reflects the limited power that these professional bodies actually wield over their members and the wider industry.

All of this means that there is no simple checklist of things a programmer should do or not do to be sure of acting ethically. Sometimes the broad imperatives have been applied generally to particular narrow contexts, as in the don’t be a dick guide to data privacy, but even this is not without contention. The guide says nothing about coercion, intentional or otherwise. Indeed even its title may not be considered professional.

Forget Computers

The appropriate and ethical action in any situation depends on the people involved in the situation, the interactions they have and the benefits or losses incurred, directly or indirectly, through those interactions. Such benefits and losses are not necessarily financial. They could relate to safety, health, affirmation of identity, realisation of desires and multitudinous other dimensions. This is the root cause of the complexity described above, the reason why there’s no algorithm for ethics.

To evaluate our work in terms of its ethical impact we have to move away from the technical view of the system towards the social view. Rather than looking at what we’re building as an application of technology, we must focus more on the environment in which the technology is being applied.

In fact, to judge whether the software we create has any value at all we should ignore the technology. Forget apps and phones and software and Java and runtimes and frameworks. Imagine that the behaviour your product should evince is supplied by a magic box (or, if it helps you get funded, a magic cloud). Would people benefit from having that box? Would society be better off? What about society is it that makes the magic box beneficial? Would people value that box?

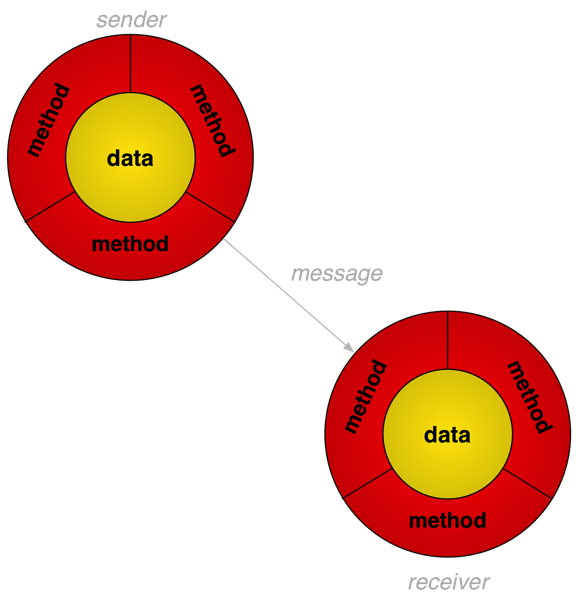

Ultimately people who make software are arbiters of interactions between people. The software is just an accident of the tools we have at our disposal. As people go through life they engage in vastly diverse interactions, assuming different roles as the situations and their goals dictate. When we redefine “making good software” to mean “helping people to achieve their goals”, we can start to think of the ethical impact of our work.

Maintaining Motorcycles

In an email discussion, a friend recently expressed the difficulty that software consultants can face in addressing this important social side of their work. Often we’re called in to provide technical guidance, and our engagement never addresses the social utility of the technical solution.

As my consultant friend put it, we put a lot of effort into the internal quality of the product: readability of the code, application of design patterns, flexibility, technology choices and so on. We have less input, if any, on the questions of external quality: fitness for purpose, utility, benefit or value to the social environment in which it will be deployed, and so on.

I think this notion of internal and external quality maps well onto the themes of classical and romantic quality described in Robert M. Pirsig’s book, Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance. And that this tension between romantic and classical ideas of quality is the true meaning behind Steve Jobs’s discussion of the “intersection of technology and the liberal arts”.

I have certainly seen this tension firsthand. I’ve been involved in a couple of engagements where the brief was to design an app to help customers navigate some complicated decision – a product choice in one case, a human-machine interface in another. The solution “just make the decision easier” was not considered once I had proposed it.

Sometimes we’re engaged for such short terms that there isn’t time to understand the problem being solved beyond a superficial level, so we have no choice but to accept that the client has done something reasonable regarding the external qualities of the solution.

The Inevitable Aside on User Stories

If we accept that people adopt different roles transiently as they go through society’s myriad interactions, and that we are aiming to support people in fulfilling these roles where ethically appropriate, then we must design software to be sensitive to these roles and the burdens, benefits and values attached to them.

This means avoiding the use of other, long-term, vague labels to define roles that are only accidentally valid. You probably know where this is going: I mean roles like user, administrator, or consumer. Very few people identify as a user of a computer. Plenty of people are users of computers, but this is an accident of the fact that getting things done in their other roles involves using a computer. It’s an accidental role, due to the available technology.

Describing someone as a user can attach implicit, and probably incorrect, values to their place in the social system. Someone identified as a computer user evidently values and derives benefit from using a computer. Their goal is to use the computer more.

A Merciful and Overdue Conclusion

Plenty that can be considered unethical is done in the name of computing. The question of what is ethically appropriate is both complex and situated, but the fundamental interconnectedness of all things means we cannot hide from the issue behind our computers. We cannot claim that we just build the things and others decide how to use them, because the builders are complicit in the usage.

While it can appear difficult for software consultants to do much beyond working on the technical side of the problems (the internal quality), in fact we have a moral imperative to investigate the social side and are often well placed to do so. As relative outsiders on most projects we have a freedom to make explicit and to question the tacit assumptions and values that have gone into designing a product. Just as we don’t wait for managerial permission to start writing tests or doing good module design, so we shouldn’t await permission to explore the product’s impact on the society to which it will be introduced.

This exploration is absolutely nothing to do with source code and frameworks and databases, and everything to do with humans and societies. Programming is a social science, at the intersection of technology and the liberal arts.

A Colophon on Professional Standards

What has all software got in common? No-one expects any of it to work. You might find that a surprisingly strong and negative statement to make, but you probably also agreed to a statement like this at some recent time when acquiring a software product:

: YOU EXPRESSLY ACKNOWLEDGE AND AGREE THAT USE OF THE LICENSED APPLICATION IS AT YOUR SOLE RISK AND THAT THE ENTIRE RISK AS TO SATISFACTORY QUALITY, PERFORMANCE, ACCURACY AND EFFORT IS WITH YOU. TO THE MAXIMUM EXTENT PERMITTED BY APPLICABLE LAW, THE LICENSED APPLICATION AND ANY SERVICES PERFORMED OR PROVIDED BY THE LICENSED APPLICATION (“SERVICES”) ARE PROVIDED “AS IS” AND “AS AVAILABLE”, WITH ALL FAULTS AND WITHOUT WARRANTY OF ANY KIND, AND APPLICATION PROVIDER HEREBY DISCLAIMS ALL WARRANTIES AND CONDITIONS WITH RESPECT TO THE LICENSED APPLICATION AND ANY SERVICES, EITHER EXPRESS, IMPLIED OR STATUTORY, INCLUDING, BUT NOT LIMITED TO, THE IMPLIED WARRANTIES AND/OR CONDITIONS OF MERCHANTABILITY, OF SATISFACTORY QUALITY, OF FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE, OF ACCURACY, OF QUIET ENJOYMENT, AND NON-INFRINGEMENT OF THIRD PARTY RIGHTS. APPLICATION PROVIDER DOES NOT WARRANT AGAINST INTERFERENCE WITH YOUR ENJOYMENT OF THE LICENSED APPLICATION, THAT THE FUNCTIONS CONTAINED IN, OR SERVICES PERFORMED OR PROVIDED BY, THE LICENSED APPLICATION WILL MEET YOUR REQUIREMENTS, THAT THE OPERATION OF THE LICENSED APPLICATION OR SERVICES WILL BE UNINTERRUPTED OR ERROR-FREE, OR THAT DEFECTS IN THE LICENSED APPLICATION OR SERVICES WILL BE CORRECTED. Source: Apple

Or something like this when you started using some open source code:

THE SOFTWARE IS PROVIDED “AS IS”, WITHOUT WARRANTY OF ANY KIND, EXPRESS OR

IMPLIED, INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO THE WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY,

FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE AND NONINFRINGEMENT. IN NO EVENT SHALL THE

AUTHORS OR COPYRIGHT HOLDERS BE LIABLE FOR ANY CLAIM, DAMAGES OR OTHER

LIABILITY, WHETHER IN AN ACTION OF CONTRACT, TORT OR OTHERWISE, ARISING FROM,

OUT OF OR IN CONNECTION WITH THE SOFTWARE OR THE USE OR OTHER DEALINGS IN

THE SOFTWARE. Source: OSI

So providers of software don’t believe that their software works, and users (sorry!) of software agree to accept that this is the case. Wouldn’t it be the “professional” thing to have some confidence that the product you made can actually function?