UIKonf 1995 Keynote : Object-Oriented Programming in Objective-C

Introduction

Welcome to the keynote for UIKonf 1995. I’m really excited for what 1995 will bring. Customers are upgrading to last year’s OpenStep release, which means that we get to use the new APIs and the best platform around. And really, there are no competitors. OS/2 Warp doesn’t seem to be getting any more traction than previous versions, and indeed Microsoft seems to be competing against its own products with Windows. Their biggest release this year, the delayed Windows 93, looks like being a warmed-over version of MS-DOS and Windows 3, which certainly can’t be compared with a full Unix system like OpenStep. 1995 will go down in history as the year of NeXT on the desktop.

I want to talk about a crisis in software design, and that is the object-oriented crisis. Well, I suppose it isn’t really, it’s the procedural crisis again. But now we pretend that our procedural code is object-oriented, and Objective-C is the weapon that enacts this travesty.

What’s the main benefit of Objective-C over Smalltalk? It’s C. Rather than attempt to graft some foreign function interface onto Smalltalk and make us write adaptors for all of our C code, Brad Cox had the insight that he could write a simple message-sending library and a syntax preprocessor on the C language, and let us add all of the object-oriented programming we’d get from Smalltalk on top of our existing C code.

What’s the main drawback of Objective-C over Smalltalk? It’s C. Rather than being able to rely on the object-oriented properties of programs to help us understand them, we can just write a load of C code that we wrap up in methods and call it “object-oriented”. This is the source of our crisis. In 1992, Brad Cox claimed that Object-Oriented Programming (or Message/Object Programming as he also called it) was “the silver bullet” that Fred Brooks claimed didn’t exist. That it would help us componentise software into isolated units that can be plugged together, like integrated circuits bought from a catalogue and assembled into a useful product on a circuit board.

This idea of encapsulated software components is not new, and was presented at the NATO conference on software engineering in 1968. At that conference, Doug McIlroy presented an invited paper called “Mass-Produced Software Components” in which he suggested that the software industry would not be “industrialised” until it supported a subindustry of comprehensible, interchangeable, well-specified components. Here’s the relevant quote, the gendered pronouns are from the original.

The most important characteristic of a software components industry is that it will offer families of routines for any given job. No user of a particular member of a family should pay a penalty, in unwanted generality, for the fact that he is employing a standard model routine. In other words, the purchaser of a component from a family will choose one tailored to his exact needs. He will consult a catalogue offering routines in varying degrees of precision, robust- ness, time-space performance, and generality. He will be confident that each routine in the family is of high quality — reliable and efficient. He will expect the routine to be intelligible, doubtless expressed in a higher level language appropriate to the purpose of the component, though not necessarily instantly compilable in any processor he has for his machine. He will expect families of routines to be constructed on rational principles so that families fit together as building blocks. In short, he should be able safely to regard components as black boxes.

Is Object-Oriented Programming actually that silver bullet? Does it give us the black-box component catalogue McIlroy hoped for? Most of us will never know, because most of us aren’t writing Object-Oriented software.

I think this gulf between Object-Oriented design and principles as described during its first wave by people like Alan Kay, Brad Cox, and Bertrand Meyer is only going to broaden, as we dilute the ideas so that we can carry on programming in C. When I heard that a team inside Sun had hired a load of NeXT programmers and were working on a post-Objective-C OO programming environment, I was excited. We know about the problems in Objective-C, the difficulties with working with both objects and primitive types, and the complexity of allowing arbitrary procedural code in methods. When the beta of Oak came out this year I rushed to request a copy to try.

Java, as they’ve now renamed it, is just an easier Objective-C. It has garbage collection, which is very welcome, but otherwise is no more OO than our existing tools. You can still write C functions (called static methods). You can still write long, imperative procedures. There are still primitive types, and Java has a different set of problems associated with matching those up to its object types. Crucially, Java makes it a lot harder to do any higher-order messaging, which means that if it becomes adopted we’ll see a lot more C and a lot less OO.

The meat

I thought I’d write an object-oriented program in modern, OPENSTEP Objective-C, just to see whether it can even be done. I won’t show you all the code, but I will show you the highlights where the application looks strongly OO, and the depths where it looks a lot like C. I don’t imagine that you’ll instantly go away and rewrite all of your code, indeed many of you won’t like my style because it’s so different from usual Objective-C. My hope is that it gives you a taste of what OOP can be about, inspires you to reflect on your own approach, and encourages you to take more from other ideas about programming than some sugar that superficially wraps C.

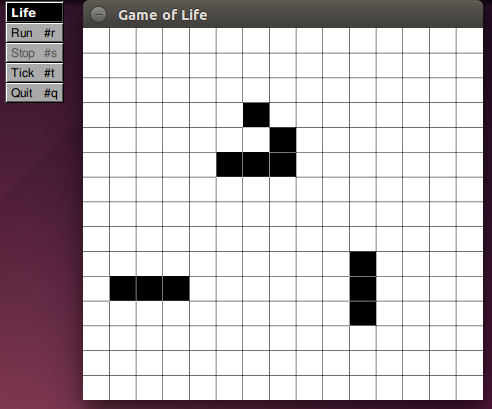

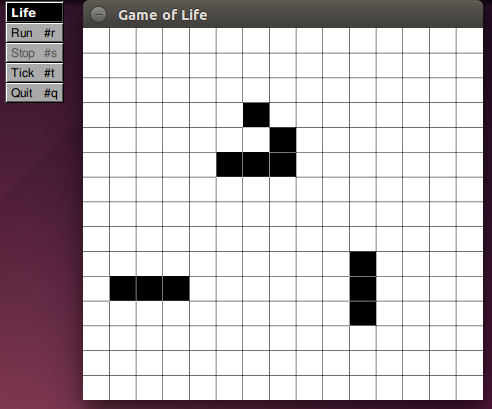

Despite a suggestion from Marvin, the paranoid android, I’m going to talk to you about Life.

Always be returning

Every method in this application returns a value, preferably an object, except where that isn’t allowed due to assumptions made by the OpenStep frameworks. Where the returned object is of the same type, the client code should use the returned object, even if the implementation is to return self. Even things that look like mutators follow this pattern: with the effect that it doesn’t matter to a client whether an object is mutable or immutable because it’ll use it the same way. Compare a mutable object:

-setFoo:aFoo

{

foo = aFoo;

return self;

}

with an immutable one:

-setFoo:aFoo

{

return [self copyWithReplacementFoo:aFoo];

}

and the client doesn’t know which it’s using:

[[myThing setFoo:aDifferentFoo] doSomeStuff];

That means it’s easy to change the implementation between these two choices, without affecting the client code (which doesn’t need to assume it can keep messaging the same object). In Life, I built a mutable Grid class, but observed that it could be swapped for an immutable one. I didn’t need to change the app or the tests to make it happen.

This obviously has its limitations, but within those limitations is a great approach. If multiple objects in a system share a collaborator, then you need to choose whether that collaborator is mutable (in which case all correlated objects see all updates, even those made elsewhere in the system) or immutable (in which case collaborating objects will only see their own updates, unless some extra synchronisation is in place). Using the same interface for both lets you defer this decision, or even try both to understand the implications.

Always be messaging

In this Life application there are no C control statements: no if, no for, no while. Everything is done by sending messages to objects. Two examples are relevant, and both come from the main logic of the “game”. If you’ve seen the rules of Life, you’ve probably seen them expressed in a form like this:

If a cell is dead and has X neighbours, it becomes living otherwise it remains dead. If a cell is living and has Y neighbours, it remains living otherwise it becomes dead.

It seems that there are three if statements to be written: one to find out whether a cell is living or dead, and another in each branch to decide what the next state should be.

The first can be dealt with using the class hierarchy. A class (at some theoretical level what I mean here is “a constructor”, but that term is not really used in Objective-C so I’m going to say “class” which is the closest term) can often be a substitute for an if statement, by replacing the condition with polymorphism.

In this case, the question “is a cell living or dead” can be answered by sending a message to either a DeadCell or a LivingCell. The question disappears, because it was sent to an object that pre-emptively knew the answer.

@interface LivingCell : Cell

@end

@interface DeadCell : Cell

@end

Now each can answer the question “what is my next state?” without needing to test what its current state is. But how to do that without that other if statement? There’s a finite number of possible outcomes, keyed on an integer (the number of living neighbours the cell has), which means it’s a question that can be answered by sending a message to an array. Here’s how the Cell does it.

-tickOnGrid:grid atX:(NSInteger)x y:(NSInteger)y;

{

return [[self potentialStates]

objectAtIndex:

[self neighboursOnGrid:grid atX:x y:y]];

}

Each of the two subclasses of Cell knows what its potential states are:

static id nextStatesFromLiving;

+(void)load

{

nextStatesFromLiving = [[NSArray alloc] initWithObjects:

deadCell,

deadCell,

livingCell,

livingCell,

deadCell,

deadCell,

deadCell,

deadCell,

deadCell,

nil];

}

-potentialStates { return nextStatesFromLiving; }

Why write the program like this? To make it easier to understand. There’s an idea in the procedural programming world that the cyclomatic complexity – the number of conditions and loops in a function – should be minimised. If all a method is doing is messaging other objects, the complexity is minimal: there are no conditional paths, and no loops.

My second example is how a loop gets removed from a method: with recursion, and appropriate choice of target object. One of the big bones of contention early on in NeXT’s use of Objective-C was changing the behaviour of nil. In Smalltalk, this happens:

nil open.

MessageNotUnderstood: receiver of "open" is nil

In Objective-C, nothing happens (by default, anyway). But this turns out to be useful. Just as the class of an object can stand in for conditional statements, the nil-ness of an object can stand in for loop termination. A method does its thing, and sends itself to the receiver of the next iteration. When that receiver becomes nil, the message is swallowed and the loop stops.

All loops in Life that are based on doing something a certain number of times are based on a category method on NSNumber.

@implementation NSNumber (times)

-times:target perform:(SEL)action

{

return [self times:target perform:action withObject:nil];

}

-times:target perform:(SEL)action withObject:object

{

return [[self nonZero] realTimes:target

perform:action

withObject:object];

}

-realTimes:target perform:(SEL)action withObject:object

{

[target performSelector:action withObject:object];

return [[NSNumber numberWithInteger:[self integerValue] - 1]

times:target perform:action withObject:object];

}

-nonZero

{

return ([self integerValue] != 0)?self:nil;

}

@end

Notice that the conditional expression doesn’t violate the “no if statements” rule, because it’s an expression not a statement. There’s one thing that happens, that yields one of two values. The academic functional programming community recently rallied around the Haskell language, which provides the same distinction: no conditional statements, easy conditional expressions.

Never be sequencing

Related to the idea of keeping methods straightforward to understand is ensuring that they don’t grow too long. Ideally a method is one line long: it returns the result of messaging another object. Then there are a couple of slightly larger cases:

- a fluent paragraph, in which the result of one message is the receiver for another message. If this gets too deep, though, your method probably has too many coupled concerns associated with a Law of Demeter violation.

- something that would be a fluent paragraph, but you’ve introduced a local variable to make it easier to read (or debug; Objective-C debuggers are not good with nested messages).

- a method sends a message, then returns another more relevant object. Common examples replace some collection object then return

self.

Finally, there are times when you just can’t do this because you depend on some API that won’t let you. A common case when working with AppKit is methods that return void; you’re forced to sequence them because you can’t compose them. The worst offender in Life is the drawing code which uses AppKit’s supposedly object-oriented API, but which is really just a sequence of procedures wrapped in message-sending sugar (that internally use some hidden context that was set up on the way into the drawRect: method).

float beginningHorizontal = (float)x/(float)n;

float beginningVertical = (float)y/(float)n;

float horizontalExtent = 1.0/(float)n;

float verticalExtent = 1.0/(float)n;

NSSize boundsSize = [view bounds].size;

NSRect cellRectangle =

NSMakeRect(

beginningHorizontal * boundsSize.width,

beginningVertical * boundsSize.height,

horizontalExtent * boundsSize.width,

verticalExtent * boundsSize.height

);

NSBezierPath *path = [NSBezierPath bezierPathWithRect:cellRectangle];

[[NSColor colorWithCalibratedWhite:[denizen population] alpha:1.0] set];

[path stroke];

[[NSColor colorWithCalibratedWhite:(1.0 - [denizen population]) alpha:1.0] set];

[path fill];

The underlying principle here is “don’t make a load of different assignments in one place”, whether those are explicit with the = operator, or implicitly hidden behind message-sends. And definitely, as suggested by Bertrand Meyer, don’t combine assignment with answering questions.

Higher-order messages

You’ve already seen that Life’s loop implementation uses the target-action pattern common to AppKit views, and so do the views in the app. This is a great way to write an algorithm once, but leave it open to configuration for use in new situations.

It’s also a useful tool for reducing boilerplate code and breaking up complex conditional statements: if you can’t represent each condition by a different object, represent them each by a different selector. An example of that is the menu item validation in Life, which is all implemented on the App delegate.

-(BOOL)validateMenuItem:menuItem

{

id action = NSStringFromSelector([menuItem action]);

SEL validateSelector = NSSelectorFromString([@"validate"

stringByAppendingString:action]);

return [[self performSelector:validateSelector withObject:menuItem]

boolValue];

}

-validaterunTimer:menuItem

{

return @(timer == nil);

}

-validatestopTimer:menuItem

{

return @(timer != nil);

}

-validatetick:menuItem

{

return @(timer == nil);

}

-validatequit:menuItem

{

return @(YES);

}

We have four simple methods that document what menu item they’re validating, and one pretty simple method (a literate paragraph that’s been expanded with local variables) for choosing one of those to run.

There’s no message-forwarding needed in the Life app, and indeed you can do some good higher-order messaging without ever needing to use it. You could imagine a catch-all for unhandled -validate<menuitem>: messages in the above code, which might be useful.

Objective-C’s type checks are wrong for Objective-C

Notice that all of the examples I’ve shown here have used the NeXTSTEP <=3.3 style of method declaration, with (implicit) id return and parameter types. That’s not because I’m opposed to type systems, although I am opposed to using one that introduces problems instead of solving them.

What do I want to do with objects? I want to send messages to receivers. Therefore, if I have a method that sends a message to an object, what I care about is whether the recipient can handle that message (I don’t even care whether the handling is organised upfront, or at runtime). The OPENSTEP compiler’s type checks let me know whether an object is of a particular class, or conforms to a particular protocol, but both of these are more restrictive than the tests that I actually need. Putting the types in leads to warnings in correct code more than it leads to detection of incorrect code, so I leave them out.

Of course, as with Objective-C’s successes, Objective-C’s mistakes also have predecessors in the Smalltalk world. As of last year (1994) the Self language used runtime type-feedback to inline message-sending operations (something that Objective-C isn’t doing…yet, though I note that in Java all “message sends” are inline function calls instead) and there’s an ongoing project to rewrite the “Blue Book” library to allow the same in a Smalltalk environment.

What is really needed is a form of “structural type system”, where the shape of a parameter is considered rather than the name of the parameter. I don’t know of any currently-available object-oriented languages that have something similar to this, but I’ve heard INRIA are working on an OO variant of Caml that has structural typing.

But what about performance?

It’s important to separate object-oriented design, which is what I’ve advocated here, from object-oriented implementation, which is the code I ended up with as a result. What the design gave me was:

- freedom to change implementations of various algorithms (there are about twice as many commits to production code in Life as there are to test code)

- hyper-cohesive and decoupled objects or categories

- very short and easy to understand methods

The implementation ends up in a particular corner of the phase space:

- greater stack depths

- lots of method resolutions

- lots of objects

- lots of object replacements

but if any of this becomes a problem, it should be uninvasive to replace an object or a cluster of objects with a different implementation because of the design choices made. This is where Objective-C’s C becomes useful: you can rip out all of that weird nested message stuff and just write a for loop if that’s better. Just because you shouldn’t start there, doesn’t mean you can’t end up there.

An example of this in Life was that pretty early in development, I realised the Cell class didn’t actually need any state. A Grid could tell a Cell what the surrounding population was, and the Cell was just the algorithm that encapsulated the game’s rules. That meant I could turn a Grid of individual Cells into a Flyweight pattern, so there are only two instances of Cell in the whole app.

Conclusions

I’m not so much worried for OOP itself, which is just one way of thinking about programs without turning them into imperative procedures. I’m worried for our ability to continue writing quality software.

Compare my list of OO properties with a list of functional programming properties, and you’ll see the same features: immutable values, composed functions, higher-order functions, effectless reasoning over effectful sequencing. The crisis of 1995 shows that we took our existing procedural code, observed these benefits of OOP, then carried on writing procedural code while calling it OOP. That, unsurprisingly, isn’t working, and I wouldn’t be surprised if people blame it on OOP with its mutable values, side-effecting functions, and imperative code.

But imagine what’ll happen when we’ve all had enough of OOP. We’ll look to the benefits some other paradigm, maybe those of functional programming (which are, after all, the same as the benefits of OOP), and declare how it’s the silver bullet just as Brad Cox did. Then we’ll add procedural features to functional programming languages, or the other way around, to reduce the “learning curve” and make the new paradigm accessible. Then we’ll all carry on writing C programs, calling them the new paradigm. Then that won’t work, and we’ll declare functional programming (or whatever comes next) as much of a failure as object-oriented programming. As we will with whatever comes after that.

Remember, there is no silver bullet. There is just complexity to be governed.